Torus fractures (or buckle fractures) are a common presentation to the paediatric emergency department, yet we don’t seem to agree on how best to manage them.

Some of us apply casts, some use splints, some have orthopaedic follow-up, and some have none.

What we do know is that torus fractures heal quickly.

Do they need treatment at all?

A Cochrane review in 2018 of 10 RCTs looking at the management of torus fractures found that there appeared to be little impact on patient recovery, regardless of the intervention or whether they received follow-up or removed the splint at home. However, the evidence of low, or very low, quality and therefore, a robust study with reliable evidence was felt necessary.

Who were the patients?

The FORCE study was conducted across 23 Emergency Departments across the UK. Patients were recruited between January 2019 and July 2020.

The children participating were between 4 and 15 years old with a distal radius torus fracture confirmed by x-ray. Children were excluded if they had other fractures, although a concomitant ulnar fracture did not lead to exclusion. Other exclusion criteria were: an injury over 36 hours old, any cortical disruption seen on x-ray, and any reasons that meant follow-up would not be possible, such as a language barrier, lack of internet access or developmental delay.

Of 1513 eligible patients, 965 were randomised. 459 families declined participation, 252 of which (55%) refused as they preferred rigid immobilisation, and 4 because they preferred the offer of a bandage. A further 89 families were not included due to problems with internet access, absence of legal guardian during recruitment and lack of clinician equipoise.

The sample was divided into two age groups: 4-7 years and 8-15 years.

What was the intervention?

At first, the study aimed to compare rigid immobilisation (current care) with no treatment and discharge. A family focus group carried out by the researchers suggested that the offer of no treatment at all was unacceptable, so the study was changed to compare rigid immobilisation with the offer of a bandage.

The study was an equivalence study. It aimed to ascertain whether or not there was a difference in pain relief and recovery when children were treated with a crepe bandage and immediate discharge versus rigid immobilisation and standard local follow-up.

458 (94%) participants in the “offer of a bandage” group chose for it to be applied in the Emergency Department. 451 (95%) participants in the rigid immobilisation group were given a removable splint. The remaining 5% in this group were treated with either a plaster cast (backslab or circumferential) or a soft cast.

What were the outcomes measured?

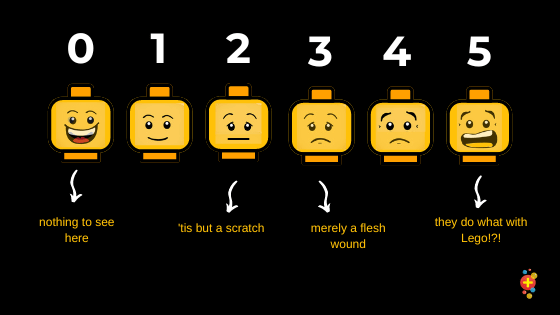

The primary outcome was pain (on day three) and was measured using the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale.

Participants also recorded their pain score on days 1, 7 and weeks 3 and 6.

Secondary outcomes were measured at these same time points, unless otherwise specified. They consisted of the following:

- Functional recovery using the PROMIS (Patient Report Outcomes Measurement System) Upper Extremity Score – a patient or parent-reported measure of physical function of the upper limbs.

- Health-related quality of life outcomes, using a EuroQol EQ-5DY a standardised questionnaire, suitable for children, which asks about quality of life, including activities of daily living and pain.

- Analgesia use and type taken (measured on days 1, 3 and 7)

At the six-week follow-up they also reported on:

- Days of school absence

- Health care resource use i.e. a new splint (measured at weeks 3 and 6)

- Return to hospital

- Treatment satisfaction – measured using a 7-item Likert scale (measured on day 1 and week 6)

What were the results?

There was no statistically significant difference in pain scores at day 3 – the primary outcome measure. Both treatments were equivalent, in terms of pain relief, at all other time points..

There was some crossover between the groups. 11% of participants who were offered a bandage crossed over to the rigid immobilisation group, mainly due to pain.

There was no statistical difference between the two groups regarding secondary outcomes either (including PROMIS scores and EQ-5DY-3L utility scores). Parents in the rigid immobilisation group were more satisfied on Day 1, but there was no difference by six weeks.

There was no difference in complication rate in either group. Both treatment options led to a similar number of missed school days – around one and a half.

There was a (small) difference in analgesia use though. 83% of the bandage group had painkillers, compared to 78% in the rigid immobilisation group on the first day, though there was no significant difference down the track.

Will this change my practice? Tessa Davis

We use a Futura splint and no follow-up for buckle fractures at my hospital. We advise patients to wear it for three weeks, then have a further three weeks with no sports, and that’s it.

Sometimes there is a discrepancy between clinicians about what exactly constitutes a buckle fracture and it would be good to see this explored further. Some cases very definitely have no cortical breach, and it’s these ones that we could manage differently.

This study reinforces what I think we all feel already about these cases – buckle fractures will heal well without any intervention. But parents do seem to be reassured by having something on the arm (and we often get asked about Tubigrips).

A good next step would be to offer a bandage only. I hope we can move to make this change.

How good was the paper – CASP Checklist?

Does the study address a clearly focused issue?

Yes

Was the cohort recruited in an acceptable way?

Yes, eligible participants were identified in participating Emergency Departments and recruited by local researchers.

Was the exposure accurately measured to minimise bias?

There were two study interventions: the offer of a bandage and immediate discharge or application of rigid immobilisation and usual local follow-up. Participants were randomised using randomisation software in a 1:1 ratio. Blinding was not possible for either treating clinicians or participants, however treating clinicians were not involved in any of the follow-up.

Was the outcome accurately measured to minimise bias?

Primary and secondary outcomes were reported using an electronic data capture system. Children reported their pain to their parental proxies. They were prompted to respond via a text message or email alert at each of the time points. A follow-up phone call was then made if there had been no response.

Validated questionnaires and paediatric pain scoring systems were used to measure outcomes where possible. And the commonly used Likert scale was used to measure treatment satisfaction.

Have the authors identified all important confounding factors?

Parents were concerned about using a soft bandage instead of a rigid immobilisation. Over half of those families who declined to participate stated this as their reason.

Due to this potential pre-existing bias, and the fact that participants and parents could not be blinded to the treatment arm they were assigned, there may have been an over-reporting of the severity of pain in the bandage group. This might explain the slightly higher pain scores coupled with increased analgesia use of analgesia on day 1. However, the study found equivalence between both treatment arms and therefore any possible bias was not sufficient enough to affect the results.

Was the follow-up of the subjects complete and accurate?

There were 867 responses from the initial 965 who were randomised. 18 patients withdrew, or were withdrawn, from the study. Response rates varied across the study period.

The majority of the results were proxy responses as parents reported for their children. This seems reasonable given the age range of the children involved.

What were the results?

There was equivalence between the study groups in terms of pain and recovery.

Immediate discharge, with no follow-up, for children with torus fracture appears safe.

Do you believe the results?

Yes.

Can the results be applied to a local population?

Torus fractures of the distal radius are the most common fracture in children in the UK. These results are generalisable to our local population. In countries with similar populations and health systems, it is also likely that these results will be relevant.

Do the results fit with other available evidence?

Yes – this study does support the findings of the Cochrane review although it rated the existing evidence as low or very low quality. This study had more participants than the other 10 studies and adds to the evidence base.

What did the authors conclude and what can we take away from this study?

The authors concluded that it is safe to treat distal radius torus fractures with the offer of a soft bandage and immediate discharge as there is no difference in outcome.

Policy change needs to involve community stakeholders given pre-existing parental preference for rigid immobilisation. They also recommend future research into the creation of a tool to identify which wrist injuries do or do not require an XR.

Some thoughts from the lead investigator Prof. Dan Perry

“It is amazing to see FORCE published, as the first in a suite of collaborative RCTs run by children’s ED clinicians and children’s orthopaedic surgeons. FORCE highlights the over-treatment that happens in many parts of practice. As doctors, we always want to do something (anything) to show that we care, though sometimes doing nothing is just as good as something. We need to shift our mindset to consider buckle fractures as a wrist sprain and treat it with love and reassurance. With more research, perhaps we can move to a situation where we don’t even x-ray most wrist injuries in children.”

Selected references

Handoll, H.H., Elliott, J., Iheozor‐Ejiofor, Z., Hunter, J. and Karantana, A., 2018. Interventions for treating wrist fractures in children. Cochrane database of systematic reviews, (12).