Forget ER, forget Grey’s Anatomy. If you enjoy learning from tachycardia-inducing trauma management, this is the video for you.

Why was the video made?

One in 20 major traumas in Ireland is paediatric, with road trauma being the most common single mechanism of injury leading to death in children (NOCA, 2019). As Nuala Quinn says, the key to gold-standard management begins when the trauma happens. First screened at a paediatric major trauma training day in January 2020, this video is one of many initiatives emerging in interprofessional education in paediatric trauma management in Ireland.

Who is the video for?

Working with Dublin Fire Brigade, the team at Children’s Health Ireland at Temple Street created this stunning training resource, led by Paul Lambert from DFB and Nuala Quinn from Temple Street, for all healthcare professionals who look after children with major trauma.

What does the video show?

Starting with the prehospital management by a team of Advanced Paramedics and paramedics, the video follows the management of a critically injured child hit by a car travelling at speed. It’s clear from the outset who the prehospital team lead is.

The communication with the child is clear and reassuring. MILS is applied immediately, and a rapid Paediatric Assessment Triangle identifies rapid, shallow respirations and extensive contusions down the right-hand side. As more prehospital practitioners arrive, handovers are kept clear and concise. Oxygen is applied, blankets are put on, a collar is applied, the pelvic binder is sited, and the child is log rolled onto an extrication device.

Once in the back of the ambulance, we glimpse a comprehensive list of WETFLAG and medication calculations and a tranexamic acid (TXA) bolus of 15mg/kg is given. The lead Advanced Paramedic debates analgesia options, discounting methoxyflurane because of a potential head injury, Entonox because of chest injury and morphine because of hypotension, settling on intravenous paracetamol and ketamine. An IMIST handover is given to control.

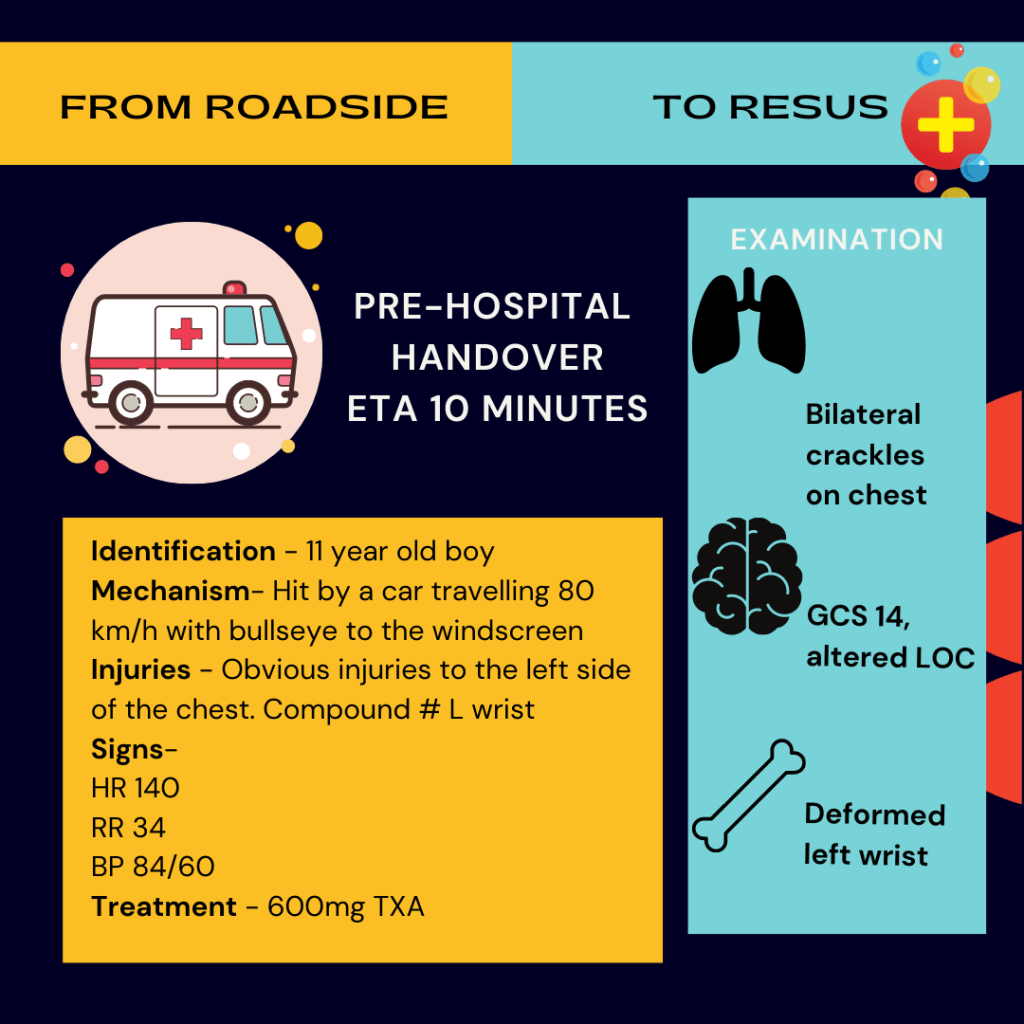

Identification: 11-year-old boy

Mechanism: Hit by a car travelling 80 km/h with a bullseye to the windscreen

Injuries: Obvious injuries to the left side of the chest with crackles on auscultation, compound fracture of the left wrist, altered LOC

Signs: Pulse 140, resp rate 34, BP 84/60, GCS 14

Treatment: 600mg TXA

ETA: 10 minutes

The video segues to Temple Street ED, where the prehospital alert is received. A trauma call is put out, and the team leader briefs the team, naming “major chest trauma with haemorrhagic shock.” A potential haemothorax requiring a chest drain, possible splenic injury and the need for resuscitation with blood are anticipated. Two plans are made: one for if the child is haemodynamically stable and one for if he is haemodynamically unstable. This is situational awareness at its best – not only is information received, but potential injuries are anticipated with alternative management plans formulated.

Next is a beautiful illustration of extremely clear role allocation with closed-loop communication. Each and every team member, from the airway doctor to the ED porter, understands their roles and responsibilities.

A plan is put in place to mitigate against the lethal trauma triad to ensure the child doesn’t become hypothermic, worsening a potential trauma-induced coagulopathy.

As the team prepares their equipment, the lead Advanced Paramedic enters ahead of the patient. There’s been a rapid deterioration: the patient’s tachy at 160, his resp rate is 28, he’s saturating at 30%, his BP has dropped to 52/36, and his GCS is now 7. At this point, I became tachycardic myself, watching the adrenaline-fuelled management of a critically unstable 11-year-old.

Against the backdrop of the all too real beeps of the monitor, a catastrophic haemorrhage secondary to a likely massive haemothorax is identified as an immediate life threat. A C-ABC trauma approach is taken.

Heart in mouth, I watched as an immediate thoracostomy was performed as soon as the child was transferred onto the bed. A gush of blood is seen, followed by blood down the chest drain. A TXA infusion is started, the first blood bolus is commenced, and the primary survey begins. The airway doctor gives a brief conscious level report and a TWELVE-C examination of the neck, naming the need for intubation.

Haemodynamics improving, a second bolus of blood is given as the primary survey doctor completes the rest of the primary survey, identifying a likely right-sided pneumothorax. A chest drain is inserted, followed by a rapid sequence induction for intubation. The airway doctor is brilliantly clear about which RSI drugs she’s choosing and why she’s choosing each dose: 1mcg/kg of fentanyl “which is 40 micrograms”, 1 mg/kg of ketamine “that’s 40 milligrams” and 1mg/kg rocuronium “40mg”.

Cardiac and lung POCUS demonstrates good contractility, bilateral lung slide and no evidence of pericardial effusion. A metabolic acidosis on gas demonstrating good evidence of tissue hypoperfusion and deranged clotting shows the child has trauma-induced coagulopathy, and the major haemorrhage protocol is activated.

While waiting for CT to become available, the child is reassessed, and the team are updated with a recap and summary. The child’s immediate life threats have been addressed. He’s haemodynamically stable and is transferred to CT.

The video ends with a verbal radiology report: normal brain, chest drains in a good position, grade 1 splenic laceration.

Throughout the whole video, you’re struck not only by the slick trauma management, anticipating and reacting to every twist and turn in the child’s resuscitation, but also by the phenomenal leadership and closed-loop communication. Trauma teams should aspire to run like this. I aspire to lead like this. This video will no doubt be an educational resource used internationally.

If you’d like to see some of Nuala Quinn’s other work on DFTB, take a look at this review she co-authored of Sarah Watt’s landmark paper on compressions in traumatic hypovolaemia and this review of Nuala’s paper, The Rule of 4s for paediatric thoracostomies and chest drains.

References

https://www.cuh.ie/2021/07/launch-of-new-paediatric-trauma-resource/

https://www.noca.ie/documents/major-trauma-audit-paediatric-report-2014-2019