What is Complex Regional Pain Syndrome?

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a chronic neuropathic pain condition characterized by spontaneous and evoked regional pain disproportionate in magnitude or duration to the typical course of pain after similar tissue trauma.

The multifactorial pathophysiology involves pain dysregulation in the sympathetic and central nervous systems, with likely genetic, inflammatory, and psychological contributions.

What symptoms should prompt the diagnosis?

CRPS is distinguished from other chronic pain conditions by the presence of signs indicating prominent autonomic and inflammatory changes in the region of pain.

- Hyperalgesia – an increased sensitivity to pain or extreme response to pain

- Allodynia – pain due to a stimulus that does not usually provoke pain

- Skin colour changes

- Skin temperature changes

- Disproportionate sweating

- Oedema

- Altered patterns of hair, skin, or nail growth in the affected region

- Reduced strength

- Tremors

- Dystonia

Diagnostic criteria

There is no gold-standard diagnostic test for CRPS in the paediatric or adult population. Making the diagnosis relies on observable signs and reported symptoms. Therefore, several diagnostic criteria have been developed. Any diagnostic tests in CRPS aim to screen for other differential diagnoses.

CRPS subtypes

- Type I

- absence of significant nerve damage

- Type II

- very rare in childhood

- occurs in the setting of known nerve damage

- CRPS-NOS (not otherwise specified)

- only partially meets CRPS criteria

- not better explained by any other condition

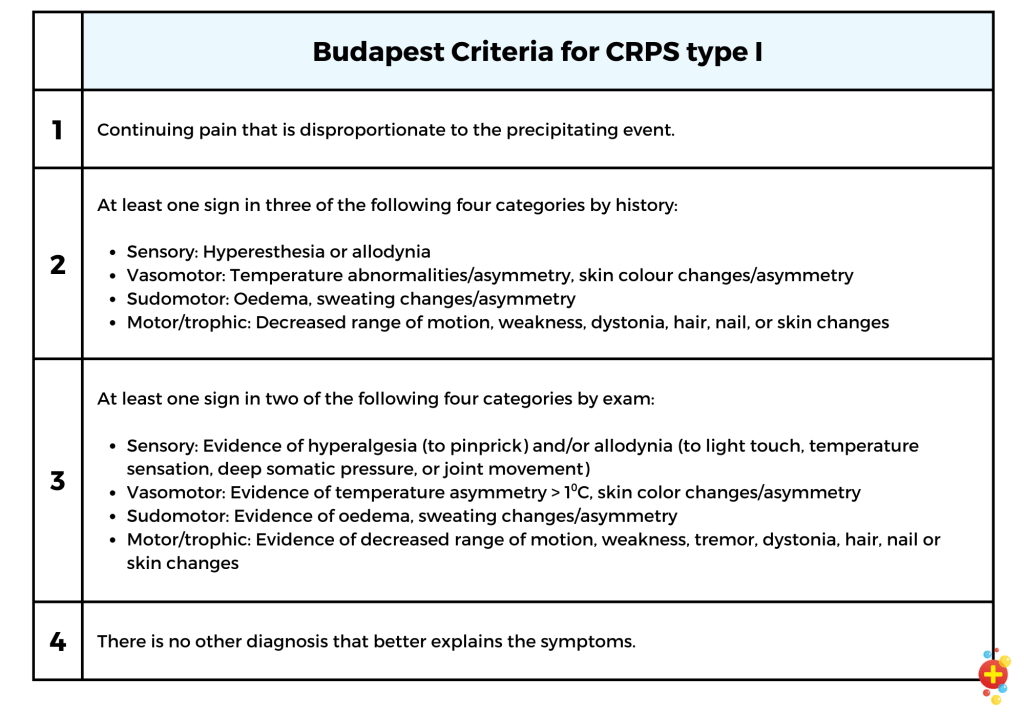

Budapest Criteria

The Budapest Criteria were suggested in 2004. Although not formally validated in the paediatric population, they have a sensitivity of almost 100% and a specificity of 70–80 % in adults.

A patient must meet all four criteria to diagnose CRPS type I.

Epidemiology of chronic regional pain syndrome

As the diagnosis of CRPS is a clinical one based on history and physical examination, there are variations between practitioners and studies. The incidence of CRPS varies between 5 and 26 per 100,000 per year, with a mean age at diagnosis of 12. The lower limbs are more commonly involved than the arms.

There is a higher incidence in:

- Females (4x more common)

- Caucasians

- Higher socioeconomic status

- Depression history

- Headache history

- History of drug abuse

What causes chronic regional pain syndrome?

Quite simply, we don’t know the specific cause of CRPS. Several neurological mechanisms for CRPS have been suggested, including central sensitisation, alteration in the central nervous system (CNS), and small fibre changes.

Pro-inflammatory states may also play a role, as patients with CRPS have significantly higher levels of plasma cytokines and chemokines. We know that fractures are the precipitating event in about 5–14% of cases and surgical procedures in 10–15%.

Stress has also been shown to play an important role in inducing and perpetuating CRPS. Children with CRPS seem to find school more stressful. They have a tendency towards over-achieving or may have learning difficulties and are more likely to have had recent psychosocial stressors.

How do we treat CRPS?

The main goals of treatment are pain relief and improvement in all domains of function, which can improve quality of life.

Management is tailored to the individual, considering the syndrome’s duration, severity, and functional impact. Early management leads to better outcomes. However, there is little evidence for the effectiveness of any given treatment modality. We don’t know how effective invasive therapies such as sympathetic blocks, epidural catheters or peripheral or plexus regional anaesthesia are in children and young people.

Any pain medications should be stopped or tapered if this is difficult. No further diagnostic tests should be organized unless new symptoms warrant them.

The ideal interdisciplinary treatment program includes intensive physical and cognitive behavioural therapy programs.

Intensive physical therapy

Increasing aerobic activity – instead of rest – is the gold standard therapy for CRPS.

A single-blinded, randomised trial of intensive physical therapy combined with cognitive-behavioural therapy for children with CRPS showed a significant improvement on five measures of pain and function, with a sustained benefit in 25 of the 28 children (95%) involved. Graded exposure to exercises that patients with CRPS think are harmful can be beneficial. Reducing pain-related fear, in turn, leads to a reduction of disability and pain.

Physical therapy programmes vary in duration, intensity and modality. They include massage, mirror therapy, electrotherapy, acupuncture, contrast baths, biofeedback, isometric strengthening exercises and recreational therapy.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

In a study by Brinkers et al. in 2018, 16% of patients diagnosed with CRPS had comorbid depression, and two-thirds had at least one psychiatric diagnosis, significantly higher than in the general population.

Children and their families should undergo a psychological assessment to understand and properly address possible individual, familial, social or academic issues.

The prognosis for children with CRPS

The prognosis for children/adolescents with CRPS is uncertain.

That being said, younger patients tend to have better outcomes with a multidisciplinary team approach leading to remission in approximately 90% of children. Relapses are common, particularly in children with more mental health difficulties at presentation.

In a 1999 study of short- and long-term outcomes in CRPS type 1 managed with physical therapy, 92% improved in the 6–8 months following an intensive exercise program. A small, retrospective review by Brooke et al. in 2012 of 19 children with CRPS treated with CBT and physical therapy showed that 89% eventually had full symptom resolution.

More recently, Mesaroli et al. carried out a retrospective chart review of children with CRPS presenting to a paediatric Chronic Pain Clinic in Canada over a 5-year period (2012 to 2016). They identified 59 children with CRPS—87% experienced complete resolution or significant improvement of CRPS, with a relapse rate of 15%. In addition to nonpharmacological treatments such as physiotherapy and psychological therapy, 79% were also prescribed medication, most commonly gabapentin.

References

Bayle-Iniguez X., Audouin-Pajot C., Sales de Gauzy J., et al.: Complex regional pain syndrome type I in children. Clinical description and quality of life. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2015; 101: pp. 745-748.

Brinkers M, Rumpelt P, Lux A, Kretzschmar M, Pfau G. Psychiatric Disorders in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS): The Role of the Consultation-Liaison Psychiatrist. Pain Res Manag. 2018 Oct 17;2018:2894360. doi: 10.1155/2018/2894360. PMID: 30416634; PMCID: PMC6207853

Brooke V, Janselewitz S. Outcomes of children with complex regional pain syndrome after intensive inpatient rehabilitation. PM R. 2012;4(5):349–54.

Bruehl S. Complex regional pain syndrome. BMJ. 2015;351:h2730. Published 2015 Jul 29. doi:10.1136/bmj.h2730

Chang C, McDonnell P, Gershwin ME. Complex regional pain syndrome – False hopes and miscommunications. Autoimmun Rev. 2019;18(3):270-278. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2018.10.003

Goldschneider KR: Complex regional pain syndrome in children: Asking the right questions. Pain Res Manag 2012; 17:386–90

Harden RN, Oaklander AL, Burton AW, et al. Complex regional pain syndrome: practical diagnostic and treatment guidelines, 4th edition. Pain Med. 2013;14(2):180-229. doi:10.1111/pme.12033

Harden, R. N., Bruehl, S., Perez, R. S., Birklein, F., Marinus, J., Maihofner, C., Lubenow, T., Buvanendran, A., Mackey, S., and Graciosa, J. (2010). “Validation of proposed diagnostic criteria (the “Budapest Criteria”) for complex regional pain syndrome.” PAIN, 150(2), 268-274. These criteria are described in the IASP Classification of Chronic Pain.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430719/

International Association for the Study of Pain. Classification of chronic pain. 2nd edition (revised).

Kessler A, Yoo M, Calisoff R. Complex regional pain syndrome: An updated comprehensive review. NeuroRehabilitation. 2020;47(3):253-264. doi:10.3233/NRE-208001

Lee BH, Scharff L, Sethna NF, McCarthy CF, Scott-Sutherland J, Shea AM, Sullivan P, Meier P, Zurakowski D, Masek BJ, Berde CB. Physical therapy and cognitive-behavioural treatment for complex regional pain syndromes. J Pediatr. 2002 Jul;141(1):135-40. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.124380. PMID: 12091866

Mesaroli G, Ruskin D, Campbell F, Kronenberg S, Klein S, Hundert A, Stinson J. Clinical Features of Pediatric Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: A 5-Year Retrospective Chart Review. Clin J Pain. 2019 Dec;35(12):933-940. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000759. PMID: 31490205

Sherry DD, Wallace CA, Kelley C, Kidder M, Sapp L. Short- and long-term outcomes of children with complex regional pain syndrome type I treated with exercise therapy. Clin J Pain. 1999;15(3):218–23.

Taylor SS, Noor N, Urits I, et al. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review [published correction appears in Pain Ther. 2021 Jul 26;:]. Pain Ther. 2021;10(2):875-892. doi:10.1007/s40122-021-00279-4

Vescio A, Testa G, Culmone A, et al. Treatment of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome in Children and Adolescents: A Structured Literature Scoping Review. Children (Basel). 2020;7(11):245. Published 2020 Nov 20. doi:10.3390/children7110245

Weissmann R, Uziel Y. Pediatric complex regional pain syndrome: a review. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2016;14(1):29. Published 2016 Apr 29. doi:10.1186/s12969-016-0090-8

Zernikow B, Wager J, Brehmer H, Hirschfeld G, Maier C. Invasive treatments for complex regional pain syndrome in children and adolescents: a scoping review. Anesthesiology. 2015;122(3):699-707. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000000573