We know that the immediate first aid of a burn is to apply cool running water for at least 20 minutes. Fiona Wood reminded us of this in her talk at DFTB18. But just how much evidence is there for its benefit in children?

This prospectively gathered cohort study looked to see if there was any association between the proper use of running water and the need for skin grafting.

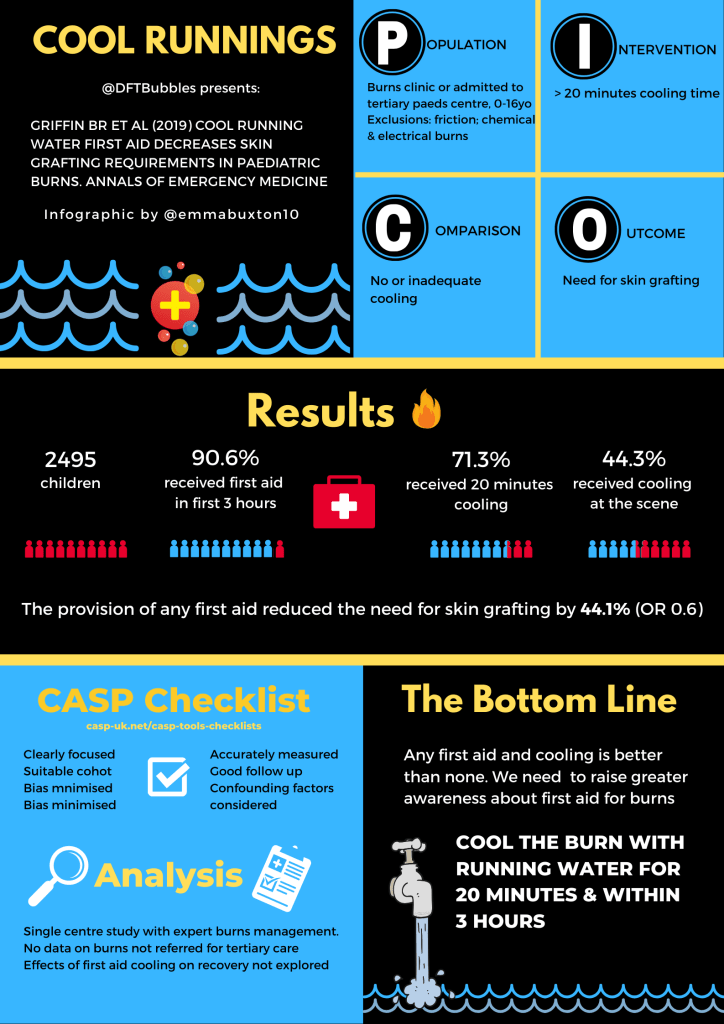

Griffin BR, Frear CC, Babl F, Oakley E, Kimble RM. Cool running water first aid decreases skin grafting requirements in pediatric burns: a cohort study of two thousand four hundred ninety-five children. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2019 Aug 29.

Some basics to get you started

According to Douglas Jackson’s 1953 model of burn injury, the point of initial heat causes irreversible damage with denaturation of protein and localized tissue necrosis. This zone of coagulation is surrounded by an area of potentially reversible damage, the zone of stasis. Around this area, there is an area of tissue that shows increased blood flow and inflammation – the redness of the zone of hyperaemia.

Population

All patients seen in the burns clinic at a tertiary paediatric centre between zero and sixteen years of age as well as those admitted to the ward service over the study period. If the burn was caused by friction, chemicals or electricity the patient was excluded from the study.

Intervention

Although the degree of first aid applied was broken down into six categories, the intervention of interest was greater than (or equal to) 20 minutes of cool running water.

Comparison

This simple intervention was compared to patients who had no, or inadequate, first aid measures. This included those that had other measures – ice, cold compresses, toothpaste(!).

Outcome

The primary outcome measure was the need for skin grafting. This served as a surrogate marker for burn severity.

Let’s take a look at the quality of the study

I’m a big fan of checklists when it comes to critical appraisal so I’m using the CASP checklist for cohort studies.

Did the study address a clearly focused issue?

Yes – Are patients with adequate cooling (defined as at least 20 minutes of cool running water) less likely to need skin grafting?

Was the cohort recruited in an acceptable way?

Yes – all patients seen by the burns service between July 2013 and June 2016.

Was the exposure accurately measured to minimise bias?

The use of any first aid measures during the first three hours was recorded at the initial interview. This typically took place three days after the burn. One might suspect that parents or caregivers would overestimate the duration of cooling or be reluctant to admit that they performed no first aid measures. In order to reduce the possibility of recall bias, the investigators performed an informal validation study in which they compared the interview responses to ED notes, referral letters and ambulance paperwork.

Was the outcome accurately measured to minimise bias?

Yes – patients either needed skin grafting or they didn’t.

Have the authors identified all important confounding factors?

The authors looked at possible confounders such as socio-economic class, type of injury, body part involved as well as the size of the burn.

Have they taken into account the confounding factors in the design/analysis?

Yes – all of the data were collected prospectively.

Was the follow-up of subjects complete enough?

All patients were followed up until epithelialization had taken place.

Was the follow-up of subjects long enough?

Yes.

2495 children were entered into the study and 2259 (90.6%) received first aid with cool running water though only 1780 (71.3%) received it for 20 minutes or more.

236 children (9.5%) required skin grafting. 58.9% (139/236) of these had adequate first aid.

As you might expect the typical patient is a young boy, around 2 years of age, who has sustained a scald to to the upper limbs.

Around 90% had some form of first aid with cool water within the first three hours of injury though only 71.3% had the recommended 20 minutes or more. A disappointingly low 44.3% had that cooling done at the scene, suggesting that 991 children did not receive anything until they reached a healthcare facility.

The provision of any first aid reduced the chances of needing grafting by 44.1% (OR 0.6). The authors used fancy statistical techniques such as logistic regression to determine if the lack of adequate first aid equated to meaningful outcome measures. They concluded that in burns that did not require grafting the median time to re-epithelialization (10 days) was not affected by the provision of adequate first aid.

But the main public health message should be that any first aid appeared to reduce the likelihood of a full-thickness burn. The odds of having a full-thickness burn were 62.6% lower in those children that received adequate first aid. Alternative treatments such as ice, cold compresses, Tiger Balm or butter are not effective. Any amount of cooling reduced the need for operative intervention (including debridement, skin grafting, escharotomies, steroid injections or dressing changes under anaesthetic) by 42.4%.

This is a single-centre study that takes place at a centre with expertise in burns management. We deal with a large number of burns in my paediatric emergency department that do not get referred to the plastics/burns service but are managed in-house. What we don’t have is the data on the burns cases that were not referred to outpatients. Clearly, these would be less significant burns, but how many of these did not have adequate first aid? There is no way of knowing what the denominator truly is. Ideally, the investigators would compare the management of all patients with a diagnosis of ‘burn and/or scald’ in the ED rather than the already selected group that goes on to require more intense treatment. With that caveat in mind, I am much more interested in parsing out the differences between those patients that required skin grafting.

Having said that my feeling is that we need to continue with the important public health message that burns should be cooled for at least 20 minutes (with cool running water) and that this should take place up to 3 hours post-injury. If a patient arrives in the ED and has had no treatment or inadequate treatment, and they are within this timeframe it should be instituted at triage if at all possible. As well as reducing pain it may well also reduce morbidity in terms of time to re-epithelialization and the need for skin grafting. It is worth noting, though, that a study in adults (Harish et al. 2018) did find a significant association with reduced time to re-epithelialization.

When discussing first aid with clinicians and the public, however, the authors recommend they shoot for exactly 20 minutes, since research led by Fiona Wood in 2016 found that cool running water is less effective or possibly even detrimental at lengths of 30 minutes or longer.

We’ll end with some final thoughts from the authors…

…We recently submitted for peer review a follow-up paper focusing on the adequacy of first aid provided by paramedics, general practitioners, and emergency department clinicians in the management of paediatric burns. This is the first part of a much larger initiative to identify barriers to the delivery of cool running water first aid by emergency providers. The findings of the study discussed here and others demonstrate that cool running water therapy must be prioritised in initial burns care, yet large proportions of children who present to emergency departments within three hours of their injury continue to receive inadequate cooling. In collaboration with emergency clinicians, we hope to figure out why this is the case and to develop strategies aimed at facilitating improved adherence to guidelines.

There were relatively few challenges in conducting the study itself. It’s true we were concerned about recall bias, which was the impetus for performing the informal validation study. The greatest challenge we’ve encountered over the course of this research has actually been the resistance and indifference we’ve faced from several clinicians in response to our results.

After we presented our preliminary findings at a surgical conference, for instance, there was little excitement that an intervention so simple, accessible, and cheap was associated with such significantly improved clinical outcomes.”Can we really expect people to run burns under water for that long?” one doctor asked. “I probably wouldn’t do it. And I don’t know if I would ask my patients to, either.” Another clinician remarked, “That’s a lot of water. Don’t you think it’s wasteful?”. Notably, neither clinician expressed any reservations about our methodology or statistics or concerns over clinical risks such as hypothermia. Instead, they were ideologically opposed to a first-aid measure consisting of 20 minutes of cool running water.

We have often wondered whether the problem for these clinicians lies in the simplicity of the intervention; immersion in running tap water might appear almost too basic to yield a substantial impact.

In addition to the attitudinal barriers, one emergency clinician from a major tertiary burns centre commented that they simply could not apply CRW as their shower room was being used for storage.

With any luck, our ongoing research will provide greater insight into the origins of such attitudes and environmental barriers, as well as solutions by which to address them.

Cody Frear and Bronwyn Griffin

Here is a great infographic summary of some of our thoughts on the paper, created by Emma Hudson:

Great article. I really liked how you broke it down with PICO and CASP, really useful. Thanks.

Thanks for the update, It’s a bit like adding a CPR coach to minimise downtime and ensure adequate depth and rate of compression. Why would we embrace something so simple that brings about an enormous difference in CPR quality?