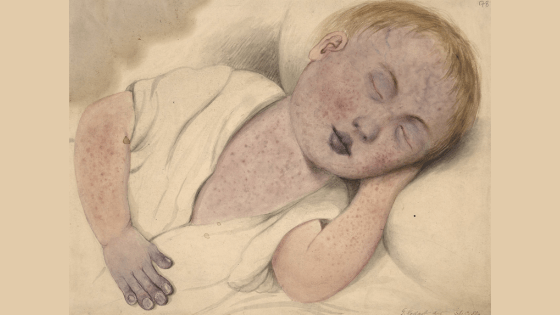

11-month-old Bella is brought to your emergency department. She’s had three days of cough with fears over 40C, conjunctivitis. Today she developed a bright red rash along her hairline.

Although you’ve never seen a case, you think it might be measles.

“It would be unfortunate if the classic sign of Koplik spots passed into history without a good facsimile of their appearance and a historical record of their description. As the use of measles vaccine grows more frequent and world-wide, future generations of physicians may not often see this important prodromal sign of measles. Already, many young North American physicians answer in the negative when asked ig they have ever actually seen these spots.”

Brem 1972

Measles is caused by paramyxoviridae.

It was considered the ‘first‘ in the classical list of childhood febrile exanthems (Scarlet fever, rubella, ‘fifth disease’ et al.). It was first described by the Persian physician ar-Razi (Razes) in 910 AD in his “Treatise on the Small Pox and Measles”.

Measles was traditionally a disease of the city, with smaller outbreaks in rural or regional communities often more severe. There was a long-held tradition of describing measles as ‘mild’ or ‘mortal’- some outbreaks, notably the 1875 Fiji Measles outbreak, have had death rates over 30%.

Since the introduction of a measles vaccine in 1963, the rates in the developed world have plummeted, approaching zero. Unfortunately, in the developing world, measles still kills about 400 people a day, mostly children.

Measles occurs in several phases:

Incubation phase

After inoculation, the virus spreads to local lymphatics via the haematological route to other lymph nodes and the spleen (viremia #1).

The incubation period averages around 13 days (6-19 days). This is usually an asymptomatic period. However, children sometimes experience upper respiratory symptoms, fever and rash.

Prodrome phase

The onset of symptoms is accompanied by a second viremia. Symptoms include fever (up to 40C) and malaise, followed by cough and coryzal symptoms. Respiratory symptoms may occur, but this two to three-day prodrome usually precedes any rash, at which time symptoms severity ramps up.

Around this time, the pathognomic feature of measles, Koplik spots, may be seen. Koplik described them as “one of the most, if not the most, reliable sign of the invasion of measles”.

In addition to preceding the exanthem, Koplik spots are said to appear before maximum infectivity. Interestingly, Koplik’s original paper quotes Osler’s description of the spots but implies it is insufficient and, along with Henoch’s description, is overly focused on the pharynx.

“On the buccal mucous membrane and the inside of the lips, we invariably see a distinct eruption. It consists of small, irregular spots, of a bright red color. In the centre of each spot, there is noted, in strong daylight, a minute bluish white speck.” … “[I]t will be seen that the buccal eruption is of greatest diagnostic value at the outset of the disease, before the appearance of the skin eruption and at the outset and height of the skin eruption.”

Koplik, 1896

The measles rash

Described as morbilliform, the measles rash typically begins at the hairline and face and spreads cephalocaudally to the neck, trunk, and extremities. Imagine dropping a tin of paint on the patient; it drips down from the head. The palms and soles are spared.

Initially, the rash blanches but may include petechiae. It is sometimes hemorrhagic in appearance. The severity of the illness generally correlates with rash coverage and confluence. It fades in the same direction.

This decrudescence phase also entails a fever that peaks on day two of the rash, lymphadenopathy (which may be generalised), pharyngitis, non-purulent conjunctivitis and occasionally splenomegaly.

After three days, the rash darkens and may desquamate. By this time, there has usually been a clinical improvement.

The rash typically lasts for a total of seven days.

The period of contagiousness is taken from the appearance of the rash. It is thought to be from (day minus five) to (day plus four) of the onset of the rash.

Recovery phase

Further fever after the fourth day suggests a secondary infection or additional complication. The cough may persist for several weeks.

“But,” Bella’s parents say, “she’s immunised as per the Australian schedule!”

As per the Australian Immunisation schedule, the first dose of the measles vaccine is given at 12 months. Seroconversion rates are around 95% after the first vaccine, increasing to approximately 99% after a second vaccine.

Irrespective of her immunisation status, Bella is not yet immune to measles, relying instead on herd immunity. This is also important for children whose immune status precludes immunisation with MMR, as it is a live attenuated vaccine. These patients include children on high-dose steroids, those with HIV (and a CD4+ count <15%), or those receiving chemo- or radiation therapy.

The Australian Immunisation Handbook mentions that, if given <12 months of age, there is still a need for two doses >12 months, as persistent maternal antibodies to measles (up to 11 months) may interfere with active immunisation.

Complications of measles

Complications are more common in children, especially those less than 5 years. Around 1 in 5 children with measles will have at least one complication.

Acute otitis media occurs in 10%.

Lower respiratory tract infections occur in 6% of measles cases; pneumonia is the most common cause of death.

1 in 1000 children will have measles encephalitis, with a high mortality rate (greater than 10%).

Measles-associated immune suppression, particularly in the developing world, confers an increased mortality risk for three years post-infection.

Subacute sclerosing pan-encephalitis occurs in after 1/10,000 cases, manifesting as a progressive, eventually fatal, deterioration with ataxia and seizures, typically seven years after infection.

Differential diagnoses

Having just described a petechial rash in a febrile child, we must consider bacterial sepsis. Recall the childhood febrile exanthems:

Exanthem 2 – Group A Streptococcus

Exanthem 3 – Rubella

Exanthem 4 – likely enterovirus

Exanthem 5 – B19 parvovirus

Exanthem 6 – Roseola infantum (HHV6)

Also, mycoplasma pneumonia (the great mimic!), EBV, adenovirus or other viruses should be considered, and it is reasonable to entertain the possibility of Kawasaki disease, Henoch-Schonlein purpura or other vasculitides too.

It’s worth noting that many cases are contracted in measles-endemic areas. That is, for cases in the developed world, it is (as always) essential to elicit a travel history. Likewise, consider measles a differential diagnosis for the suspected Ebola patient in your isolation room (!).

Do we need to do any tests?

Getting measles IgM serology is not unreasonable if measles is high up the list of differentials. The measles virus can also be found in blood, throat swabs or urine via PCR. Although they might not change management, the results will give public health some leads and diagnostic clarity for the patient and their family.

If you’ve done an FBC and LFTs, you might see leukopenia, lymphopenia, and mildly raised transaminases.

How infectious is measles?

Measles can survive for up to 2 hours in the air but is rapidly inactivated by heat, light, and pH extremes. It is reasonable to assume that each case will have an associated number of contacts. In most areas, measles is a notifiable disease, and the Public Health Unit may refer contacts for post-exposure prophylaxis.

Post-exposure prophylaxis

Immunocompromised patients or those patients <9 months should receive a ‘Normal Human Immunoglobulin’ (NHIG). Patients over nine months of age, who have yet to receive their first dose of MMR vaccine, should receive a vaccine, as should those over 12 months if they’re yet to receive a second MMR vaccine, provided their first dose was more than four weeks previously.

Pregnant patients should be offered NHIG.

Bottom Line

Measles is one of the classic febrile exanthematous illnesses.

Although rare in the developed world, thanks to a good vaccination program and a historically well-understood disease process, it is still a major cause of childhood mortality worldwide.

Measles outbreaks occur sporadically in areas with close contact and lower vaccination rates.

Measles may cause fever and rash in a recently returned traveller from an endemic area.

It is very contagious, and there may be a need for large-scale post-exposure prophylaxis after a confirmed case.

Children under five and immunocompromised patients are the most vulnerable to measles and complications.

References

Baxby, Derrick (July 1997). “Classic Paper: The diagnosis of the invasion of measles from a study of the exanthema as it appears on the buccal mucous membrane”. Reviews in Medical Virology 7 (2): 71–74.

Brem, J. Koplik Spots for the Record: An Illustrated Historical Note Clinical Pediatrics March 1972 11: 161-163,

Dobson, M. Disease. Oxford: BCS Publishing (2007) pp140-6.

Kliegman R. (Ed.) Measles. Nelson Essentials of Pediatrics. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. (2013)

Koplik, H.: The diagnosis of the invasion of measles from a study of the exanthema as it appears on the buccal mucous membrane. Arch. Pediat. 13: 918, 1896.

Measles – World Health Ogranisation

Measles images via Center for Control of Disease – Public Health Image Library. https://phil.cdc.gov/phil/details.asp?pid=3168 & https://phil.cdc.gov/phil/details.asp?pid=3167 (Public domain)

Tasker, RC (Ed.) Exanthema 1; measles. Oxford Handbook of Paediatrics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (2008) pp684

The Australian Immunisation Handbook 10th Edition (2013) via: www.immunise.health.gov.au