Around 300 babies a year are born in the UK with sickle cell disease, and with 96% of them experiencing a painful vaso-occlusive crisis by the age of 8 years, it is unsurprising that these patients are frequently seen in Paediatric Emergency Departments. But are we good at looking after them?

Unfortunately, evidence suggests not.

NICE guidelines set the standards for their care, requiring a pain assessment to be made at time zero in triage, with pain relief offered within 30 minutes of arrival. Reassessments should then be undertaken every 30 minutes until pain reaches an acceptable level.

A national audit presented at the Haemoglobinopathy UK Forum in 2023 found that only 21% of adult and paediatric patients presenting to the Emergency Department with a painful crisis received analgesia within 30 minutes.

Why is this so important?

Acute pain in children is associated with fear, anxiety, somatic symptoms, and increased parental distress. For all children presenting to the Emergency Department, effective assessment and management of pain is essential. In sickle cell disease, however, it is even more critical.

Patients with sickle cell disease have a mutation in the beta globin gene on chromosome 11. The resulting haemoglobin is fragile and prone to polymerisation during deoxygenation. Polymerisation leads to the formation of rigid fibres within the red blood cells, deforming them into a sickle shape.

The sickle-shaped cells struggle to move easily through small blood vessels, leading to obstruction to blood flow, damage to the vessel walls and cell aggregation. The resulting ischaemia, and then reperfusion, damages tissues and organs and is extremely painful.

Many factors predispose a patient with sickle cell disease to having a vaso-occlusive crisis. These include illness, hypoxia, hypothermia, strenuous exercise, surgery and dehydration. Pain, and the anticipation of pain, can also cause vasoconstriction, either precipitating or worsening a vaso-occlusive crisis. This means that if we fail to treat pain adequately, the clinical picture will continue to deteriorate.

Added to this is the impact of poor pain management on future attendances.

One longitudinal qualitative study interviewing young people with sickle cell disease found that poor management of pain during hospital attendances led to reticence to attend hospital during future crises. With a 10-year cohort study demonstrating crude mortality from crises at 8%, it is unacceptable that our inadequate pain management should put patients at risk by impeding future attendances.

How do we assess acute pain in the paediatric emergency department?

Pain is subjective and its expression and experience are influenced by a vast range of factors, including age, developmental understanding and past experiences.

Traditional pain score tools that rely solely on physical attributes are limited by their momentary assessment of pain and are influenced by an individual’s pain tolerance, which can lead to potential misinterpretation. For the best understanding of a child’s pain experience, we should be relying on patient and parent-reported pain. Children in general, however, present unique challenges when it comes to self-reporting.

For very young children, the absence of verbal communication or the lack of understanding of pain concepts prevents the use of self-reporting. For those children, the FLACC (Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability) score is a good example of an observational behavioural pain scoring system which relies on clinical observation to make a pain assessment. Including parents in this assessment is essential, as they provide key insights into an individual child’s ‘normal pain cues’.

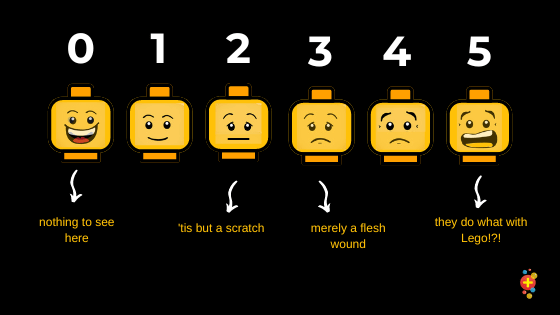

Young children often struggle with differentiating levels of pain in terms of numerical value. For these children, age-related pictorial assessment tools, such as the Wong-Baker FACES scale, provide a good starting point.

For older patients, self-reporting using a numerical scale such as the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) is the gold standard. It is essential to contextualise this for each patient by asking how it compares to their daily pain, how it is affecting their activities, and whether their pain is manageable.

The challenge of assessing acute pain in sickle cell disease

Children with sickle cell disease live with chronic pain, and this creates particular challenges when assessing acute pain. Classical numerical scales can create inconsistencies between clinicians and patients, as patients may not display typical signs and cues to their level of distress.

Children with sickle cell disease often develop individual coping strategies to manage their pain, such as watching television, playing, or sleeping. These behaviours, coupled with the absence of typical pain cues, can sometimes lead healthcare professionals to question the severity or authenticity of the pain being reported. Consequently, pain may be under-recognised and under-treated, with analgesia tapered prematurely.

Inadequate pain management can also give rise to behaviours that are sometimes misinterpreted as suspicious by healthcare professionals. These may include requesting specific analgesics or closely monitoring the timing of medication and asking for it as soon as it is due. This pattern, known as ‘pseudoaddiction’, is not indicative of true addiction and typically resolves once pain is effectively managed. At the heart of good pain management is the establishment of a trusting relationship between healthcare providers, patients, and their families.

Treating the pain

Children with sickle cell disease often develop personal non-pharmacological strategies to manage their pain, such as breathing exercises, relaxation techniques, massage, or distraction. Their presence in the Emergency Department usually signals that these home-based methods have been insufficient. Nonetheless, it is important to explore and support any self-developed coping strategies, as incorporating them into the acute care setting can foster comfort, autonomy, and trust.

Given their lifelong experience with chronic pain, many children with sickle cell disease are already taking regular analgesics and may have had frequent exposure to opioids. As such, simple analgesia alone is often insufficient, and early escalation of pain management is essential. According to NICE guidelines, children presenting with severe pain or with moderate pain despite prior analgesia should receive a bolus of a potent opioid as first-line treatment. For those requiring a repeat bolus within two hours, patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) should be considered. In most centres, this is initiated with support from the anaesthetic team.

For any patient you are starting on regular opioids, remember to consider the side effects and treat these accordingly. These include:

- Constipation

- Nausea and vomiting

- Itching

Act proactively and ensure that prescriptions for laxatives, antiemetics, and antipruritics are completed in the Emergency Department. This prevents patients struggling with symptoms on the ward during the inevitable wait for a ward Doctor to be available.

And don’t forget…..

Pain is only one aspect of the presentation in a child with sickle cell disease. It is equally important to assess hydration status, oxygenation, and the presence of any intercurrent illness. Clinicians must also remain alert to serious complications such as acute chest syndrome, abdominal sequestration, and sepsis. A systematic A–E assessment should always be the starting point, followed by a thorough history and examination. Early involvement of your local haematology team is strongly advised to guide ongoing management and prevent deterioration.

What can we do to improve things?

Education is essential. ED staff should be educated on the seriousness of reported pain in patients with sickle cell disease, the challenges around assessment, how pain may present differently and the clinical and psychological impacts of undertreated pain.

Consider up-triaging patients with sickle cell disease. This serves two purposes. It enables the prompt reassessment of pain after initial triage assessment, but it also serves to highlight to all staff the more serious nature of the patient’s presentation.

Consider a ‘sickle-cell proforma’ for use on acute admission. Whilst we can get bogged down with endless proformas, they are an excellent way to improve standards of care and can include charts with 30-minute pain score checks on, escalation plans for analgesia and other essential considerations.

Take Home Messages

Prompt pain assessment and management in sickle cell disease is essential. Patients should have their pain assessed and managed every 30 minutes.

Assessment can be challenging, but the cornerstone to effective treatment is recognising that patient and family reported levels of pain are our most accurate tool.

Expect to need to use stronger analgesia, and don’t hesitate to escalate management in order to get pain under control as quickly as possible.

References

Gill F.M., Sleeper L.A., Weiner S.J., Brown A.K., Bellevue R., Grover R., Pegelow C.H., Vichinsky E. Clinical events in the first decade in a cohort of infants with sickle cell disease. Coop. Study Sick. Cell Dis. Blood. 1995;86:776–783

Nice Clinical Guideline CG 143. Sickle cell disease: managing acute painful episodes in hospital. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg143/chapter/Recommendations#individualised-assessment-at-presentation

Sanne Lugthart, Paul Telfer. An update from the National Sickle Pain Group. 22th November 2023. Haemoglobinopathy UK Forum. https://haemoglobin.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/An-update-from-the-National-Sickle-Pain-Group-Sanne-Lugthart.pdf

American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Task Force on Pain in Infants, Children, and Adolescents. The assessment and management of acute pain in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2001 Sep;108(3):793-7. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.793. PMID: 11533354.

Chumpitazi CE, Chang C, Atanelov Z, Dietrich AM, Lam SH, Rose E, Ruttan T, Shahid S, Stoner MJ, Sulton C, Saidinejad M; ACEP Pediatric Emergency Medicine Committee. Managing acute pain in children presenting to the emergency department without opioids. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2022 Mar 12;3(2):e12664. doi: 10.1002/emp2.12664. PMID: 35310402; PMCID: PMC8918119.

Ingram V.M. A specific chemical difference between the globins of normal human and sickle-cell anaemia haemoglobin. Nature. 1956;178:792–794. doi: 10.1038/178792a0

Takaoka K, Cyril AC, Jinesh S, Radhakrishnan R. Mechanisms of pain in sickle cell disease. Br J Pain. 2021 May;15(2):213-220. doi: 10.1177/2049463720920682. Epub 2020 May 22. PMID: 34055342; PMCID: PMC8138616.

Sundd P., Gladwin M.T., Novelli E.M. Pathophysiology of Sickle Cell Disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2019;14:263–292. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012418-012838.

Brandow A.M., Carroll C.P., Creary S., Edwards-Elliott R., Glassberg J., Hurley R.W., Kutlar A., Seisa M., Stinson J., Strouse J.J., et al. American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for sickle cell disease: Management of acute and chronic pain. Blood Adv. 2020;4:2656–2701. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001851

Khaleel M, Puliyel M, Shah P, Sunwoo J, Kato RM, Chalacheva P, Thuptimdang W, Detterich J, Wood JC, Tsao J, Zeltzer L, Sposto R, Khoo MCK, Coates TD. Individuals with sickle cell disease have a significantly greater vasoconstriction response to thermal pain than controls and have significant vasoconstriction in response to anticipation of pain. Am J Hematol. 2017 Nov;92(11):1137-1145. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24858. Epub 2017 Aug 17. PMID: 28707371; PMCID: PMC5880319.

Renedo A, Miles S, Chakravorty S, Leigh A, Telfer P, Warner JO, Marston C. Not being heard: barriers to high quality unplanned hospital care during young people’s transition to adult services – evidence from ‘this sickle cell life’ research. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019 Nov 21;19(1):876. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4726-5. PMID: 31752858; PMCID: PMC6873494.

FB. Piel, M Jobanputra, M Gallagher, J Weber, SG. Laird, M McGahan. Co-morbidities and mortality in patients with sickle cell disease in England: A 10-year cohort analysis using hospital episodes statistics (HES) data. Blood Cells, Molecules, and Diseases. Volume 89, July 2021, 102567

A.L. Drendel, B.T. Kelly, S. Ali. Pain assessment for children: overcoming challenges and optimizing care. Pediatr Emerg Care, 27 (2011), pp. 773-781

K Young. Assessment of Acute Pain in Children. Clinical Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Volume 18, Issue 4, December 2017, Pages 235-241

Darbari D.S., Brandow A.M. Pain-measurement tools in sickle cell disease: Where are we now? Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program. 2017;2017:534–541. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2017.1.534

Brandow AM, DeBaun MR. Key Components of Pain Management for Children and Adults with Sickle Cell Disease. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2018 Jun;32(3):535-550. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2018.01.014. PMID: 29729787; PMCID: PMC6800257.

Stinson, J., Naser, B. Pain Management in Children with Sickle Cell Disease. Pediatr-Drugs 5, 229–241 (2003). https://doi.org/10.2165/00128072-200305040-00003

D.J. Crellin, D. Harrison, N. Santamaria, F.E. Babl. Systematic review of the Face, Legs, Activity, Cry and Consolability scale for assessing pain in infants and children: is it reliable, valid, and feasible for use? Pain, 156 (2015), pp. 2132-2151

D. Tomlinson, C.L. von Baeyer, J.N. Stinson, L. Sung. A systematic review of faces scales for the self-report of pain intensity in children. Pediatrics, 126 (2010), pp. e1168-e1198

Gai N, Naser B, Hanley J, Peliowski A, Hayes J, Aoyama K. A practical guide to acute pain management in children. J Anesth. 2020 Jun;34(3):421-433. doi: 10.1007/s00540-020-02767-x. Epub 2020 Mar 31. PMID: 32236681; PMCID: PMC7256029.

Beyer JE. Judging the effectiveness of analgesia for children and adolescents during vaso-occlusive events of sickle cell Disease. J Pain Symptom Manage 2000; 19: 63–72

Schechter NL. The management of pain in sickle cell disease. In: McGrath PJ, Finley GA, editors. Chronic and recurrent pain in childhood: progress in pain research. Vol. 13. Seattle (WA): IASP Press, 1999: 99–114

Weissman DE, Haddox JD. Opioid pseudoaddiction: an iatrogenic syndrome. Pain 1989; 36: 363–6

van Veelen S, Vuong C, Gerritsma JJ, Eckhardt CL, Verbeek SEM, Peters M, Fijnvandraat K. Efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions to reduce pain in children with sickle cell disease: A systematic review. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2023 Jun;70(6):e30315. doi: 10.1002/pbc.30315. Epub 2023 Mar 30. PMID: 36994864.